Close to Home: the title announces a body of work that is local, personal – in one of Karen Shepherdson’s own words, ‘modest’. There’s a deliberate refusal here of the portentous, a backing off from claiming too much; this is not even Blake’s world in a grain of sand, or if it is, it is good old Broadstairs sand. But in that there is also a laying claim to something that is not modest at all, the belief that if we look closely at what is close to home we will see something that really matters. These works stand against the English tendency to deprecate the capacity of the artist to speak to and of the local, reminding us of the largeness of locus in the word, as well as the smallness of the parish. This requires a certain effort from the viewer: not to pass by quickly what might appear insignificant, rather to linger and appreciate small differences in couples photographed from year to year, or to re-consider the snap of a holiday long gone, of children no longer children, in the light of its being re-read through the instant camera and the lens of the present.

There is a constant dialogue in these photographs between past and present, articulated through the technology of the instant camera. For even when the image presented comes from the past – that other country where they do things differently – it has been re-seen, re-photographed, sometimes reconfigured in the present. Shepherdson’s full use of instant film throughout ensures the awareness of that present even in the images of children so clearly located by their clothing and demeanour (home-knitted jumpers, the open gaze to camera with its lack of the self-consciousness and image-awareness of the digital age) in the 50s and 60s. That she is sometimes reconsidering images of herself and her immediate family adds poignancy to the relationship between the eye of the photographer and the reflected self which also enters the viewer’s understanding and emotional response.

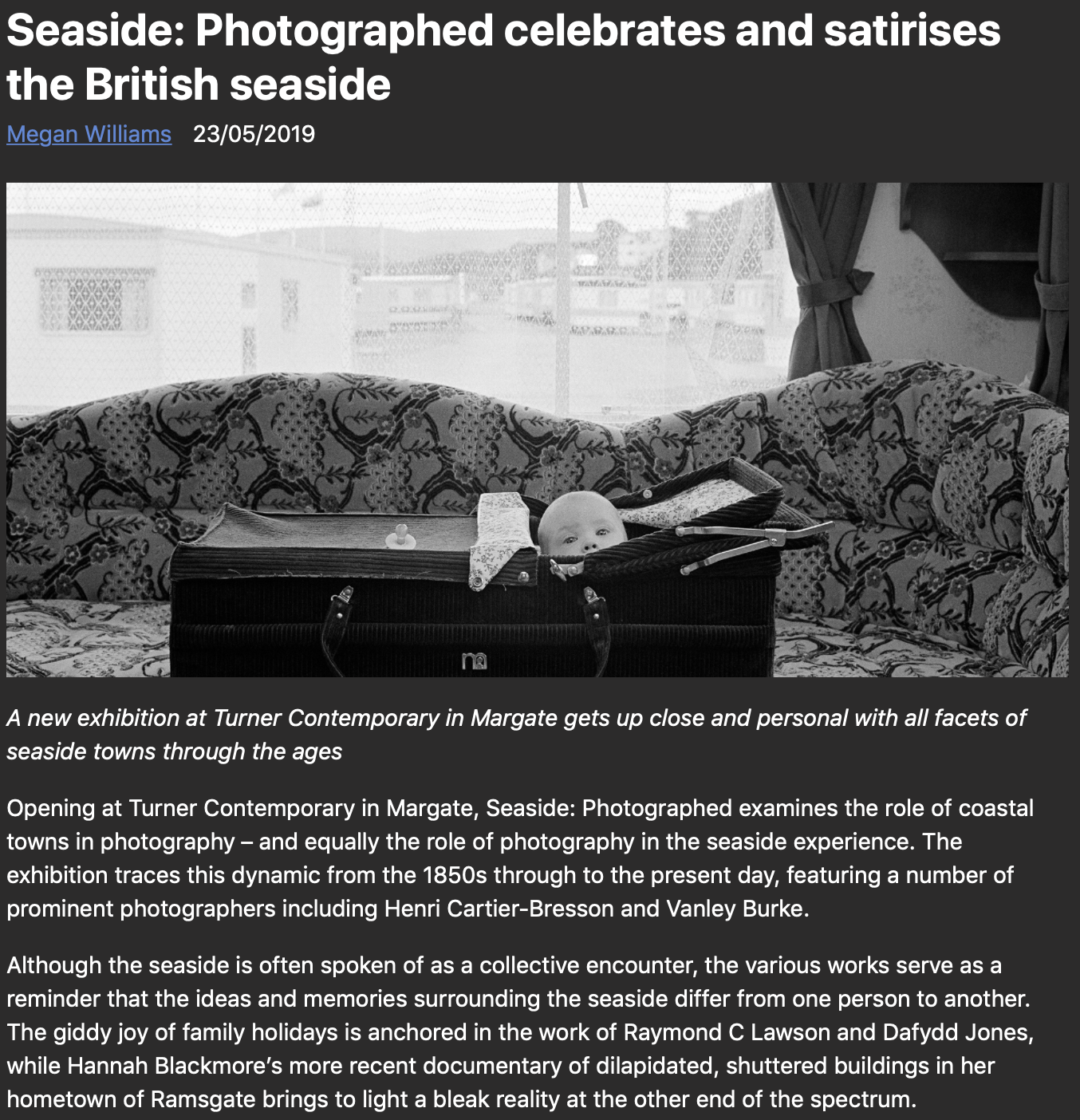

There is, of course, a real danger with these images from the past, especially those in seaside settings, with their associations of happy play and family ease beside a lapping sea, that a simply nostalgic response is not sufficiently challenged. The sea’s edge is indeed ever present in the Seaside series, in Jetty, and (implied) in the Returned series. But an edge it is, and not always a benign one; that horizon of water leaves nowhere to go. Thanet’s island origins mark it out as an unusual place, separated, other, and that sense lurks beneath the sometimes larky surface of these images.

Key to this is the insistent seriousness of composition which is marked in 100 Couples and in The Welcome Rest, where the subjects are initially random, determined only by their being in a particular place – couples who came along to The Old Lookout, people with dogs taking their ease on a particular bench on the Broadstairs jetty – but whom the photographer has marshalled and directed into a disciplined composition. The repetition of certain elements in each image reminds us of the certainty of place (the bench, the jetty where people have always walked their dogs, the sea beyond endlessly turning on each tide). The montage method of showing the prints draws attention to these constant elements but also then allows us to notice the differences between the human subjects, and the nuances of relationship in the different couples (and their changing relationship over time as some of them return to be re-photographed). The human subject is determinedly not ironised. Even the dogs – again, a subject which might invite sentimentality – are taken seriously, holding the camera in their own steadfast gaze.

In a world where everything and everyone is photographed, the instant print still maintains what Geoffrey Batchen calls ‘indexicality, this direct physical link between a photograph and the thing it represents’. The product of a low key technology and process, the instant print, unadulterated by the machinations of the digital, retains a democratic integrity. It underpins Shepherdson’s insistence on an equality and commonality across her subjects, and between herself as photographer and the photographed subject, an aesthetic which is given substance by her native knowledge of and familiarity with this place and the people who inhabit it.

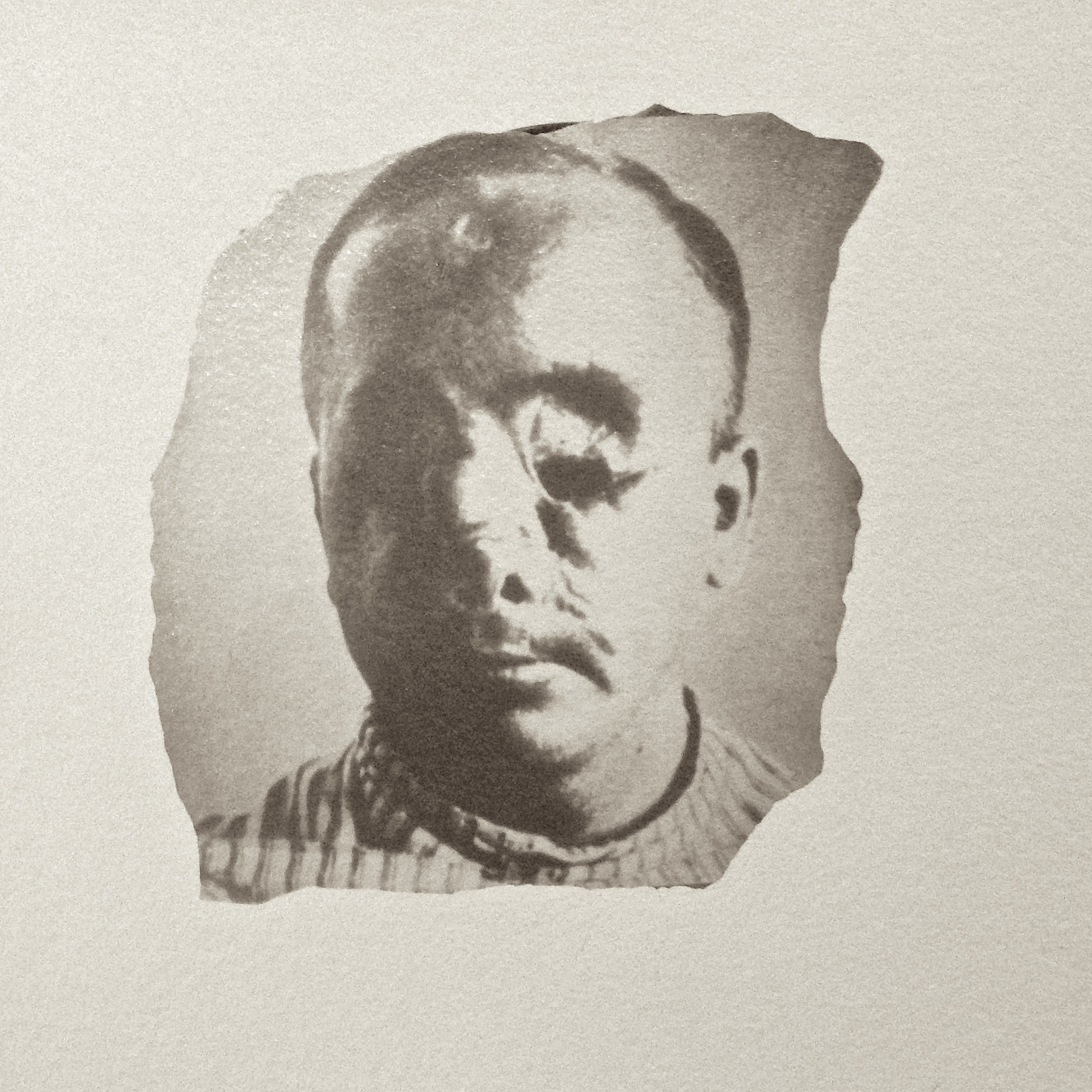

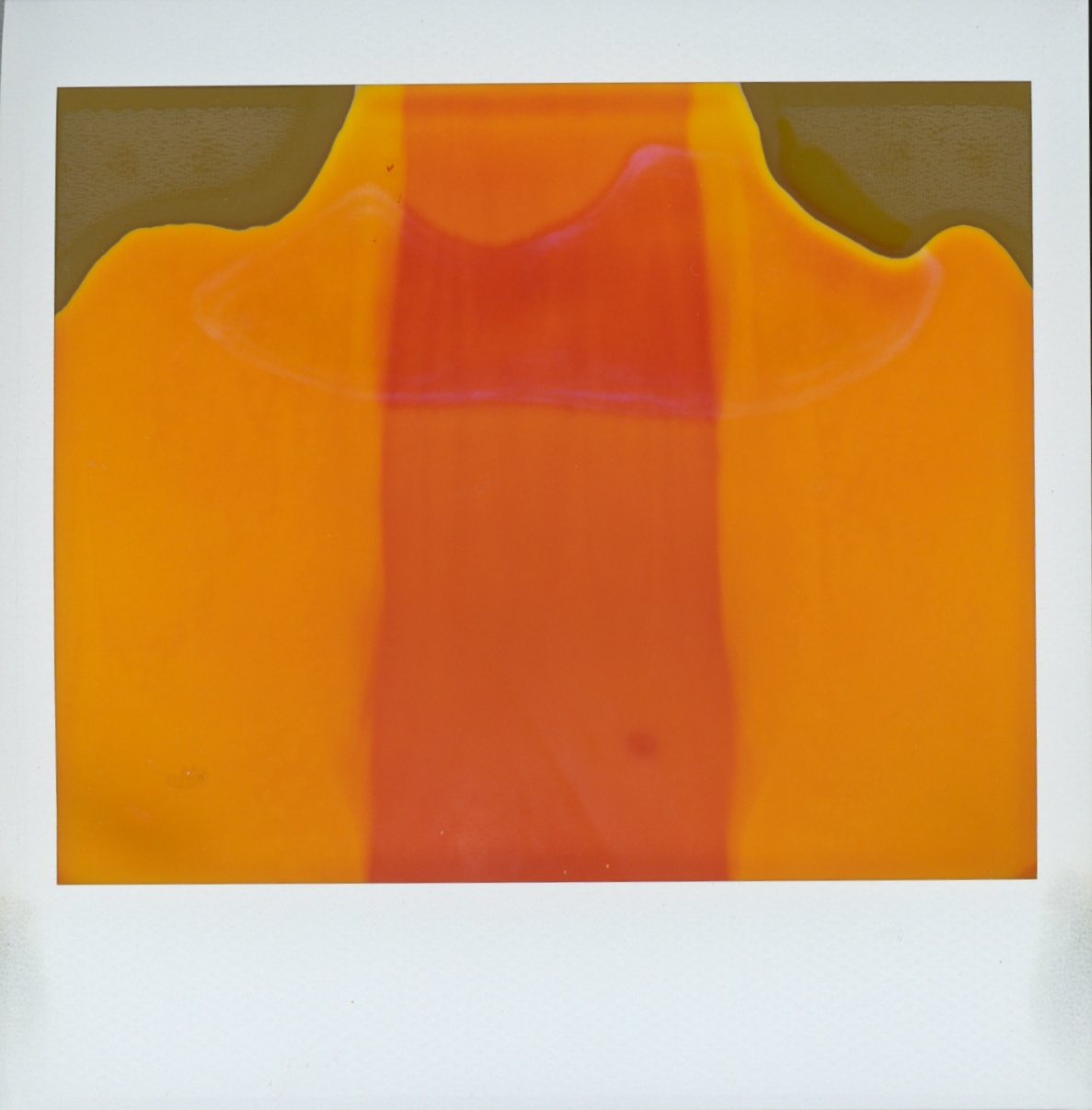

The passage of time is inherent in the human subject placed before a camera, and a long term project such as 100 Couples will, in time, embody that through its very longevity. The Punctum section images reflect on it in a more complex way, reminding us forcibly, both in their title and in themselves, of Barthes’ aperçu that ‘by giving me the absolute past of the pose … the photograph tells me death in the future. … Whether or not the subject is already dead, every photograph is this catastrophe’. Such thoughts might seem overblown as we look at 100 Couples, The Welcome Rest, Seaside and Returned, were it not for the complementary body of work which faces us much more directly with issues ofmortality. In the Palimpsest and Light series in the Jetty section, the comfort of home, recognisable horizon or landscape, the security of the body itself – these are abruptly removed, presenting the viewer with either apparent abstraction or a human image blotted out by light. Meaning, in the sense of a perceived reality captured on film, can be but dimly made out. The Palimpsest images are, with a couple of interesting exceptions, traces of nothing but the chemicals on the instant film, printed by the pressure of the roller in the instant camera. Yet when we know that this is old film, originally intended to take instant pictures of stillborn babies for their parents, that knowledge inevitably colours our response to images which are in themselves and nonetheless unconnected with those unformed lives. Whether we think that such external knowledge should be imported to the photograph, or whether we think it should stand alone, the Palimpsest images placed alongside 100 Couples and The Welcome Rest disturb their surface sense of the constancy of place and people and remind us of the void just below human existence.

That void is most movingly represented in the Echoes of Epstein photographs. Here we are brought up short against what the earlier sunny images will come to. There is a hard-eyed but compassionate understanding of the human body in its frailty, open to its own finiteness and strong in being that. These images, lifted from the surface of the instant print in a difficult, tenuous and uncertain process, are by virtue of that almost see-through, the frailty of the technique echoing the frailty of the subject. Painful as they are to confront, they are also lyrical, calling to mind Mediaeval painted wooden sculptures, which celebrate the human body while reminding us of its end.

Thus we are brought full circle, from the earliest beginnings, the blank sheet on which sometimes only an image of nothingness itself is printed, through childhood and apparent seaside happiness, the lived life, coupledom, and the sheer, odd pleasure of dogs, to completion and the admission of mortality and the trace again of nothingness through the Polaroid lift, itself a final palimpsest.