Abstract: This paper as part of the Margate PhotoFest (2015) placed into context the significant cultural role the seaside photographer has had in documenting and refracting back the beach experience. From as early as the late 1850s itinerant seaside photographers were located on the UK beaches and along with early examples, the presentation considered how the experience of the beach photographer evolved through three ages of seaside photography: early, high and contemporary and also what the future might hold for the photographer working the sands in the modern era.

Picturing Aftermath - A Visual Response to the Broken Faces of WW1

Abstract: This illustrated artist paper sought to provide insight into contemporary creative practice-based research, exploring themes of human ruin, (re)membering and remembrance. In doing so, the research specifically examined and contextualised the photographic series Aftermath (Shepherdson, 2014) which was commissioned to commemorate the centenary of the First World War’s start. Aftermath in reappropriating the found images of Ernst Friedrich’s 1924 Krieg dem Kriege examined ‘ruination’ relating to the human form, a form all too vulnerable to mechanical warfare. In addition the paper discussed how physical vulnerabilities might be translated forcefully, yet simultaneously tenderly, through images of the damaged human face.

The presentation demonstrated Aftermath’s use of the esoteric photographic technique of emulsion lifting, whereby the photographic emulsion - similar to that of a fine layer of skin - is lifted away, re-echoing the fragility of the face and the utter devastation at its loss. As Sally Minogue comments “The damaged face was one of the most difficult disfigurements for a surviving combatant to bear because of the public response of disgust and rejection, as well as the sufferer’s own deep loss of confidence and sense of identity. In facing Shepherdson’s photographs we take on a responsibility to face up to what modern warfare means” (2014:23).

A characteristic of emulsion lifts are tears and creases which subsequently require slow, gentle teasing and stroking out by hand using soft natural bristle brushes. This act of stroking and easing the face back into shape is of course in sharp distinction to the moment of facial destruction. The specificity of this process also limits scale and thus distils each work into a unique artefact with consequent ‘flaws’ accepted and welcomed. In considering photography’s potential to connote human fragility and ruin, the paper will draw upon the salient writings of Derrida, Sontag and Berger.

Remembrance and (Re)membering: contrasting perspectives on the Sunbeam Photographic Collection

(An illustrated paper presented at Archives 2.0 Conference, at the National Media Museum, Bradford, 25-26 November 2014)

Abstract: Aleida Assman stated that ‘the archive…can be described as a space that is located on the border between forgetting and remembering’ (2008:103). Both are selective processes that forge meaningful terrains and bring order to isolated artefacts. ‘(Re)membering’ is a slightly ironic concept that attempts to encapsulate the archival processes of collection and collation, synthesising disparate parts into a meaningful whole. The Sunbeam Photographic Collection is an example of this - consisting of more than 40,000 commercially taken British seaside photographs from 1917–1976. Their origins are private individuals and uncollated municipal holdings and it is the role ofthe South East Archive of Seaside (SEAS) Photography to construct an ordered collection from such disordered parts.

The archivist’s meaningful terrain represents a perspective which can be at odds with users and contributors. ‘Remembrance’ refers, in this context, to the emotional meaning that such ‘holiday snap’ images have for the non-archivist, interpreted through the lens of selected memory. For the archivist, such nostalgia gives way to categorical synthesis and academic analysis, in which technical, historical and cultural contexts predominate. Thus, far from a neutral interpretational landscape, this Collection can be regarded as a locus of contrasting and perhaps conflicting perspectives. For some contributors, key Sunbeam' images represent a canon, with overt sanctification. Accordingly, the archivist can be seen as hijacking the demotic, taking the ‘people’s pictures’ and over-intellectualising them. A central problem to be discussed is, therefore, how this nexus of conflicting perspectives is navigated/negotiated, without alienating the very people whose contributions are so vital to the archive’s formation.

Beyond the View - Reframing the Sunbeam Photographic Collection

(An introduction to Ball, R & Shepherdson K.J. (eds), 2014, Beyond the View (New) Perspectives on Seaside Photography, Burton Press.)

For much of the twentieth century the Subeam Photographic Company represented and reflected British seaside culture. As a photographic company it documented on a vast scale life on the UK’s south east coast and specifically that of the Isle of Thanet. Whilst Sunbeam are perhaps best known for their ‘seaside’ pictures, this was far from their sole genre, diversifying into capturing civic, ceremonial and political events; producing numerous idealised promotional tourist images; landscapes and townscapes; broad commercial work; school photography and even eccentric animal portraiture. As Anthony Lane noted in his detailed exposition on Sunbeam:

Not many activities can be said to capture the life and soul of a town as well as photography. Conversely, not all photographic institutions have a wide enough spectrum of interest to capture all aspects of a metropolis. One commercial company that came as close as any to achieving this aim … was Sunbeam Photo Limited. For fifty years their roving photographers ranged along the promenades, patrolled beaches, penetrated the political conferences and emerged with a wealth of pictures at work and play. (Lane 1999:293)

Sunbeam was indeed the dominant commercial photographic company on the Isle of Thanet and one of the largest in the country. It was founded by John Milton Worssell in 1919 and remained within the family under the directorship of Worssell’s two sons Richard and Jack, until 1976. As early as 1912, Worssell Snr. had gained a modest foreshore concession in Margate and between the Wars, once Sunbeam was established, rapid expansion was in evidence. From 1925 a bespoke laboratory and offices were built in Sweyn Road, Clifftonville, facilitating a factory process of standardisation. Sunbeam also had a studio in the popular Northdown Road, Clifftonville and numerous concession kiosks along the coast.

The company actively sought to differentiate itself from connotations of earlier itinerant coastal photographers and Colin Harding provides an excellent account of this in an essay accompanying this publication. Sunbeam took overt pride in training many smart young men – and later women too – for the summer season, training them not only in the practice of picture making, but also in their approach to and handling of the general public. This informal professionalism led to Sunbeam being regarded as a trusted company, whereby the photographer was perceived not as nuisance or hawker, but rather as a professional, as someone to engage with and trust.

The Company’s paternalistic philosophy is evidenced in Jack Worssell’s letter to an employee:

"…we old-timers can take satisfaction from the knowledge that the firm we served for the greater part of our respective working lives has, during its existence, provided work for a great many local people, and also been responsible for introducing many young people into the photographic industry, providing them with a solid grounding in photography which they found to be most helpful in later years (cited in Lane 1999:328)."

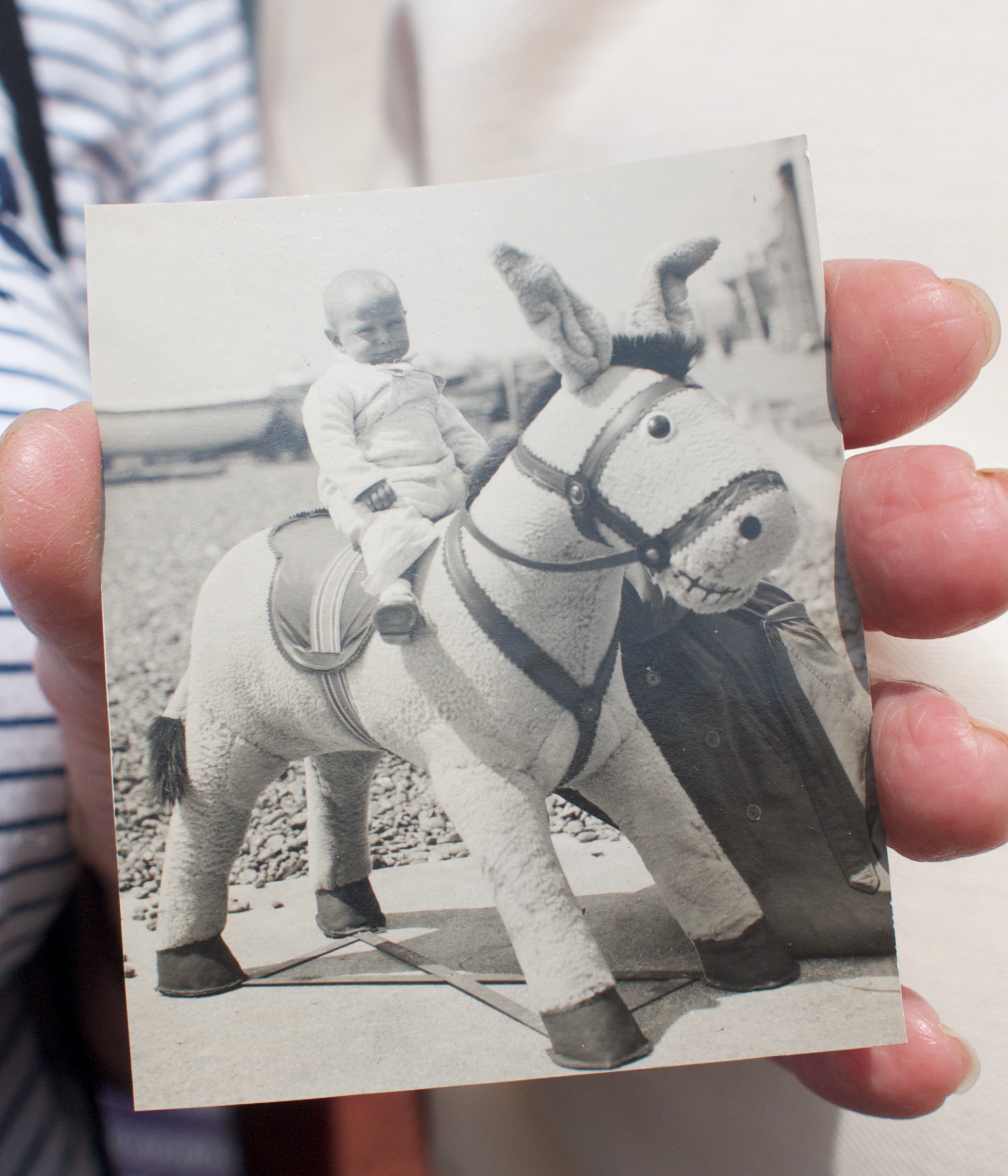

Associated with the topographical and idealised images of the British coast, the roving Sunbeam photographers throughout the summer season would be photographing holidaymakers as they walked along the promenade or sat on the beach. These images, referred to as ‘seaside photographs’ or ‘walkies’; were taken in a period when many families still did not own their own camera and thus the Sunbeam photographers offered a means of recording the family trip to the coast. These are the images that perhaps best typify Sunbeam, signifying the delights of the seaside. Countless such photographs demonstrate the Isle of Thanet in its heyday, where the promenades and beaches were crowded with visitors after making their migration to the coast. Photographed on one day and bought the next, many of these images are now found only within family albums and whilst many hundreds of thousands were taken, few actually exist within the Sunbeam Collection.

Since 2012 and in an attempt to uncover and document these privately held pictures, the South East Archive of Seaside (SEAS) Photography has organised collection points and community collection days, whereby members of the public have brought to the Archive their own commercially taken seaside photographs. The significance of these modest postcard-sized pictures has been repeatedly made manifest. An elderly couple brought a single Sunbeam image of their child who had died at a young age. Another image donated by a woman was of her mother and father taken long before her own birth – it showed her parents as a loving young couple, with, on the photograph’s back, the fading stamp of a German Prison of War insignia: ‘Stalag XXI’. The image had been sent by her mother to her father via the Red Cross after he had been captured early in WWII. Through the process of community collection it has become apparent that, more than just donors, people have become genuine contributors to and participants in the developing Archive.

In parallel with the ‘seaside photographs’ and ‘walkies’ is the Sunbeam Collection’s large number of parade and carnival images. On examination what becomes evident is how significant is the amount of effort and energy invested in not only float design, but also costume and flamboyant masquerading. Predominantly images of the 1950s and ‘60s, they signify not only a delight in masquerade and parade, but also and at times uncomfortably so, the vastly different social mores of that era. The repeated stereotyping of race, sexuality and women abounds. What would now be regarded as wholly unacceptable and offensive was considered then as playful and harmless. Many of the carnival images reward close scrutiny: faces and gestures frequently undermine a simple reading of pleasure. The children, huddled (and frequently held) with masquerading adults, often look anxious and photographs repeatedly signify Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of the carnivalesque – the idea of eccentric behaviours and familiar and free interactions between people being temporarily allowed within the public sphere. The rationale of leisure activities permits the expansion of usual normative boundaries.

The diversity of the Sunbeam Collection not only provides access to the past’s public arena, but also numerous and poignant images within the domestic sphere – drawing attention to the more passive and frequently stark home lives of the mid 20th century. These images represent a site of homemaking, of modest and often restrained celebration and a place where communities could come together to mark events such as the Coronation in 1953, or where children could use the roadside as a place of safe play, uninhibited by the interventions of adults.

It is perhaps easy to regard such collections of commercial photography as ephemeral, yet the images within the archive and this publication are worthy of reappraisal and reimagining. They provide and construct a view of seaside experience – of high days and holidays, seductively drawing us into an often idealised vision of the past. Paradoxically, such images can often be both prosaic and evocative – resonating still with many viewers. Perhaps these are the pictures which particularly signify the very potency of photography, of making the past present again. As articulated by Yves Dorme such pictures show “a second of happiness, captured forever, fixed on film. Which says hello and goodbye, both at the same time” (2007:37)

References and Suggested Reading:

Bakhtin, M. (1984) Rabelais and His World, John Wiley and Sons.

Depardon, R, and Dorme, Y. (2007) Images Cachées, Centre National de l’Audiovisuel.

Godfrey, P. (2013) Snapped at Gorleston on Sea, Suffolk.

Harding, C. ‘Sunny Snaps: Commercial Photography at the Water’s Edge’ in Ball, R. and Shepherdson, K.J. (eds.) (2014) Beyond the View: Reframing the Sunbeam Photographic Collection, Burton Press.

Lane, A. (1999) ‘Thanet Revealed: The Story of Sunbeam Photo Ltd, Part One’, in Bygone Kent, 20: 293-328

Lane, A. (1999) ‘Thanet Revealed: The Story of Sunbeam Photo Ltd, Part Two’, in Bygone Kent, 20: 323-328

Linkman, A. (1993) The Victorians: Photographic Portraits, Tauris Park.

From Smudger to Sunbeamer: Informal professionalism in commercial seaside portraiture

(An illustrated paper presented at Exchanging Photographs, Making Knowledge 1890-1970 Conference, atthe Photographic History Research Centre at De Montfort University, Leicester, 20-21 June 2014)

Abstract: The research upon which this illustrated paper is based seeks to provide insights into a somewhat overlooked form of demotic photography: the seaside ‘walkie’ or commercial seaside photograph. The research specifically examines the Sunbeam Photographic Company located in Margate, UK until the mid-1970s and whose vast collection of glass and celluloid negatives is currently being digitised at the South East Archive of Seaside (SEAS) Photography. The Sunbeam collection is providing a revealing and rich seam of imagery and offers new perspectives on commercial seaside photographic practice and technique.

This illustrated paper examines the Company’s commercial photographic practice from 1920-1970, offering an exposition of the British seaside photographer as s/he evolves from the itinerant individual to resident employee within an organised structure. The role of seaside photographer had often been couched in derogatory terms such as ‘Smudger’ or ’Bungler’ and generally regarded as an inept and relentless seaside pest. Yet Sunbeam provides an example of a commercial photographic company located at the coast, which strategically countered the negative connotations orbiting the seaside photographer. Sunbeam sought to revise public perception through a variety of methods including the employment of articulate, well-groomed and proficient photographers – both men and women – projecting an overt professionalism cloaked in informality. A system was devised by Sunbeam that was calculated to standardise customer experience and where differentiation of that experience occurred it would be safely located at the margins. For example, through the benign use of elaborate props such as stuffed lions, bears and tigers; large Disney figures; or farcical ersatz elephants, donkeys and dogs. The consequences of this standardisation are arguably images, which facilitate an increased informality by the sitter(s) and whereby the prosaic pictures produced resonate still with the contemporary viewer- signifying the very potency of photography, in making the past present again.

Beyond the View: Reframing the Early Commercial Seaside Photograph

(An illustrated paper presented at Oxford University, Coastal Cultures of the Long Nineteenth Century Conference)

Abstract: For the latter part of the 19th and much of the 20th Century, commercial photographers represented and reflected the heritage of British seaside culture. The research upon which this paper is based, seeks to provide insight into an overlooked form of demotic photography, revealing rich seams of imagery and offering fresh perspectives on Victorian coastal representations.

The paper examines commercial seaside photographic practice from 1860-1920, offering a visual exposition of the British seaside, as represented through the refracted lens of the itinerant ‘beach’ photographer – also often derogatorily referred to as a ‘Smudger’. Despite their humble means of production, the photographs shown are frequently evocative, drawing the viewer into a nostalgic past shaped by visual half-truths. Photographic half-truths that too readily can become amplified from a view to the view and to the experience.

The research presented here examines the conventions, expectations and mythologisations of what seaside portrait photography of this period should present and how these inevitably provide a highly mediated and edited view of the actual Victorian seaside experience. Here I attempt to reframe and recontextualise these ‘seaside snaps’, providing visual and text-based content that rewards both scrutiny and critical engagement.